Two decades after his death, Serge Gainsbourg's Parisian home has opened as a museum. Dorian Lynskey takes a dive into the complicated, musical and Jewish roots of the great man

In 1969, the same year his mischievously erotic single ‘Je T’aime… Moi Non Plus’ sold six million copies and was denounced by the Vatican, French Jewish songwriter Serge Gainsbourg bought a house at 5 bis rue de Verneuil in Paris’s chic 7th arrondissement. It took two years to refurbish it to his exacting specifications (everything black: walls, floors, ceilings, furniture) but after that he stayed put, right up until 2 March 1991, when he died in bed of heart failure at the age of 62.

Gainsbourg’s former partner, actor and singer Jane Birkin OBE, compared life with him to “living in a museum” because he insisted that nothing was moved or (ideally) even touched. After his death, it was left exactly as it was, with the piano lid open, a record on the turntable and cigarette butts in the ashtrays. Now, after 20 years of setbacks, the house will finally open its doors to the public in early 2022, thanks to the efforts of actor and musician Charlotte Gainsbourg, daughter of the late singer and Birkin. Maison Gainsbourg includes not just the house but also, at 14 bis rue de Verneuil, a museum, bookstore, gift shop and cafécum-piano bar called Le Gainsbarre.

The venue is named after the demonic, hard-drinking alter ego that Gainsbourg adopted in the 1980s, claiming that “when Gainsbarre gets drunk, then Gainsbourg disappears”. But Serge Gainsbourg was itself an alias used by the man who was born Lucien Ginsburg to Russian Jewish immigrants in 1928. “Gainsbarre used to laugh about Gainsbourg and mock Ginsburg, but they were always there inside him, like a Russian doll,” Birkin explained of his alter egos to the musician’s biographer, Sylvie Simmons.

Maison Gainsbourg © Alexis Raimbault

Gainsbourg’s parents Joseph and Olia Ginsburg fled Ukraine after the Russian Revolution in 1917 and settled in Paris, where they were determined to become French and leave the old world behind. The Ginsburgs did not attend synagogue or keep a kosher home, settled far from other Jewish immigrants, and gave their second son, born with a twin sister, the classically French name Lucien. “I would have loved to have had roots,” Gainsbourg later said. “To be a man you need roots. I am rootless.”

Joseph’s integrationist dream did not survive the Nazi invasion of France. He lost his job as a nightclub pianist and his family were forced to wear yellow stars. “It was like you were a bull, branded with a red-hot iron,” his son remembered. You might see the rest of his life as a rebellion against ever being categorised and constrained again. Unsafe in Paris, the Ginsburgs used forged papers under the name Guimbard to flee to Limoges – in the Vichy ‘free zone’ – and did not return until the liberation of the city in 1944. Olia’s brother, not so lucky, died in Auschwitz.

After the war, Gainsbourg enrolled at art school and became a painter, teaching the children of Holocaust survivors, while understudying for his father in Parisian piano bars. Music ultimately won out. “He didn’t want to be a second-class painter, he wanted to be a first-class songwriter,” said Birkin. When he registered with SACEM, the French songwriters’ society, in 1954, it was as Serge Gainsbourg, splitting the difference between his family name and that of one of his favourite painters, Thomas Gainsborough. “Serge” represented the Russia he never knew.

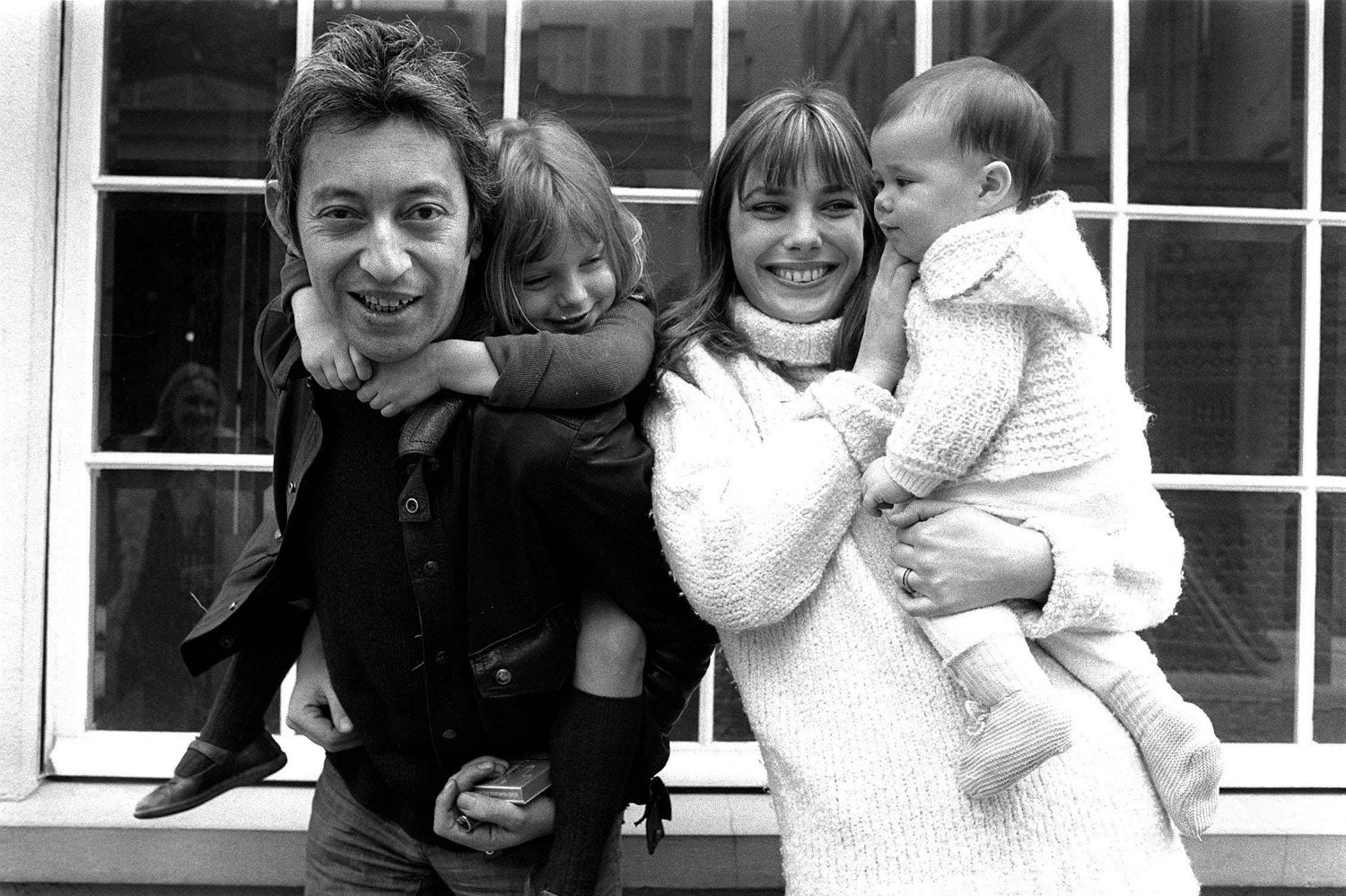

Serge Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin with baby Charlotte and Birkin’s late daughter Kate Barry, May 1972 © Alamy

Gainsbourg had a musical life like no other, even before you consider his parallel career as an actor, director and soundtrack composer. His own existentialist jazzpop, thick with literary references and shocking black comedy, was hailed by one critic in 1959 as “something new, bizarre, tormented, deep and ultra-modern. Love him or hate him, you’re going to have to recognise that Serge Gainsbourg is somebody.” But his weak voice and stage fright meant that he began to thrive only when he wrote for other vocalists, starting with the chanteuses Michèle Arnaud and Juliette Gréco. After ‘Poupée de Cire, Poupée de Son’ – sung by France Gall – won Eurovision for Luxembourg in 1965, he wrote hits for stars such as Sacha Distel and Françoise Hardy, as well as French bombshell Brigitte Bardot, who became one of his many extramarital lovers.

Divorced twice by 1966, Gainsbourg once described his life as “an equilateral triangle, shall we say, of Gitanes [cigarettes], alcoholism and girls”. Tabloid mockery of how he looked arm-in-arm with various celebrated beauties reminded Gainsbourg of the antisemitic abuse he had received as a teenager in wartime Paris. His response was typically witty: “Ugliness has more going for it than beauty does: it endures.

After ‘Je T’aime…’, was written for Bardot but recorded with his new lover, Birkin. The song made him rich and (in)famous at the unusually tardy age of 41, Gainsbourg recorded his masterpiece, 1971’s Histoire de Melody Nelson. This spokenword concept album’s rich, cinematic arrangements have since been homaged by artists including Air, Beck and the Arctic Monkeys, but his most commercially successful record was something else entirely: 1979’s Aux Armes Et Caetera made him the first white artist to record a reggae album in Jamaica. In the 1980s he pivoted again, this time to funk, new wave and a shaky impression of hip-hop. Even in the ’60s, he’d been experimenting with sampling, lifting everything from African rhythms to Dvorák. For all the sex, scatology and satire in his lyrics, Gainsbourg thought that the common thread in his music was a strain of melancholy: “My music is Judeo-Russian: always something sad.”

Maison Gainsbourg exterior © Alexis Raimbault

On his 1975 album Rock Around the Bunker, Gainsbourg finally addressed his wartime trauma, albeit in the bizarre form of satirical rock’n’roll with titles such as ‘Nazi Rock’ and ‘Yellow Star’. It was “clearly an exorcism,” he said. Around that time, he commissioned Cartier to make him a platinum replica of that star, as if to turn enforced shame into defiant pride. When the title track of Aux Armes Et Caetera, a reggae version of the French national anthem La Marseillaise, caused a national scandal, Gainsbourg’s concerts were picketed by the far right and novelist Michel Droit accused him of “provoking” antisemitism. Gainsbourg responded that the national anthem was nothing if not revolutionary. Two years later, single ‘Juif et Dieu’ (‘Jew and God’) was released, a sardonic celebration of world-changing Jews including Marx, Einstein, Trotsky and Jesus. “And what if God was Jewish?” he asks in the opening line. “Would that worry you…?”

To his critics, Gainsbourg could never be truly French. He was always other. Yet to his fans, who were legion, Gainsbourg became a national icon despite his myriad eccentricities and contradictions. In many respects he was a fastidious control freak, with a hatred of drugs and a neurosis about dirt. “I want to order everything,” he would tell Birkin before she tired of his micromanaging ways and left him in 1980. At the same time, he was a chronic alcoholic who smoked five packs of Gitanes a day and, during his final Gainsbarre period, made outrageously messy appearances on chat shows. He caused uproar by burning a banknote as an anti-tax protest and by propositioning a horrified Whitney Houston. His record sales suffered, although he continued to write for actor-singers (Isabelle Adjani, Vanessa Paradis) and even managed to cowrite a second-place Eurovision entry in 1990. It was called ‘Black and White Blues’ after singer Joëlle Ursull understandably vetoed his original title, ‘Black Lolita Blues’.

Serge Gainsbourg at 5 bis rue de Verneuil in Paris, January 1972 © Alamy

Perhaps only in France could such a proudly delinquent character become a national treasure, loved for his flaws as much as his strengths. Gainsbourg’s place in French culture was confirmed by the extraordinary reaction to his death. Flags flew at halfmast, President Mitterrand compared him to Baudelaire and Apollinaire, and fans covered the walls of 5 bis rue de Verneuil with tributes. The house instantly became a shrine and so it has remained for 30 years. “The house belongs to me, but it will never belong to me,” Charlotte Gainsbourg said recently. “It’s his home.” During the long years when French bureaucracy thwarted her efforts to open it to the public, she wondered if it should remain frozen in time, but ultimately she decided that it needed to become part of the life of Paris.

Serge Gainsbourg professed not to care how he was remembered. “I don’t want to go down in posterity,” he said. “What has posterity ever done for me? Fuck posterity.” Nonetheless, he inspired an all-star tribute album in 2006 and an award-winning biopic in 2010. Now the excitement surrounding Maison Gainsbourg is testament to the resilience of his reputation. At various points in his life he was bullied, stigmatised, pilloried and abused, but in the end he became indelibly, quintessentially French, his identity defined by nobody but himself. He planted his own roots.

By Dorian Lynskey

Maison Gainsbourg is located at 14 rue de Verneuil, 75007, Paris. It is open daily; reservations must be made in advance online. maisongainsbourg.fr

This article appears in the Autumn 2021 issue of JR.