‘Yiddisher jazz’ was once all the rage in London’s East End, so where did it go? Alan Dein reports

“Music is the most beautiful language in the world,” proclaimed Weinberg’s gramophone shop in the 1920s. This formed the basis of one of their adverts in a Yiddish language newspaper once sold on the streets of Whitechapel. At the time, swinging dance bands were all the rage and local venues like St George’s Town Hall, Grand Palais and the People’s Palace proudly hosted jazz dances, complete with live bands and foxtrot competitions. At Levy’s record store on Whitechapel High Street, which was known both locally and further afield as “the home of music”, customers could find the latest jazz imports and even discs pressed on Levy’s own record labels, Levaphone and Oriole.

This was a landscape where generations of gifted young Jewish East Enders – musicians, impresarios, club and record shop owners – would go on to forge a remarkable contribution to the development of the British music scene. These include Ronnie Scott, Lionel Bart, Bud Flanagan, Alma Cogan, Georgia Brown, Joe Loss and Stanley Black, to name but a handful. Their legacies can be found easily in a few clicks online, but surprisingly, given the Jewish cultural and religious backdrop, what has proved far more elusive to track down are physical Jewish-themed jazz and dance band discs or folk and musical comedy numbers recorded in London between the 1920s and 1950s. There’s no problem in finding their equivalents in the US, or even the Jewish dance music from pre-Nazi era Germany or Poland. So my quest was to seek out and rescue the ‘Yiddisher jazz’ soundtrack of the old Jewish East End from aural oblivion and release them in a new collection: Music is the Most Beautiful Language in the World.

I found some remarkable 78 rpm discs in the archives of the British Library and Jewish Museum London, several records in private collections, and I even spotted extremely rare examples in charity shops in Hendon and Golders Green.

It’s inevitable that such discarded treasures would emerge in the districts where former Jewish East Enders settled and after all these years the recordings preserved within the shellac grooves perfectly evoked the joy and vigour of my grandparents’ generation.

I’ve devoted most of my working life to music history and making sound recordings and I’m convinced that audio has a unique power to conjure up the soul and atmosphere of a past world. It almost mirrors the old time Yiddish theatre performances, where audiences would experience an emotional rollercoaster, inevitably leaving them both smiling and welling up.

We can delight in the cheeky street patter of the slapstick drummer Max Bacon, rejoicing in the East Enders’ love affair with doughy rolls, recorded for Decca in 1935. Bacon’s ‘Beigels’ is a fabulous Whitechapelset rumba and was one of a series of playful musical sketches he performed in ‘Yinglish’, a cod European/Cockney mash-up of Yiddish and English. Other titles included ‘Shmoul, Pick Up the Kishke’, ‘Cohen the Crooner’ and ‘I Can Get it For You Wholesale’. And take Bacon’s word for it – on this side of the pond, the dough with the hole is pronounced ‘by-gel’, not ‘bay-gel’.

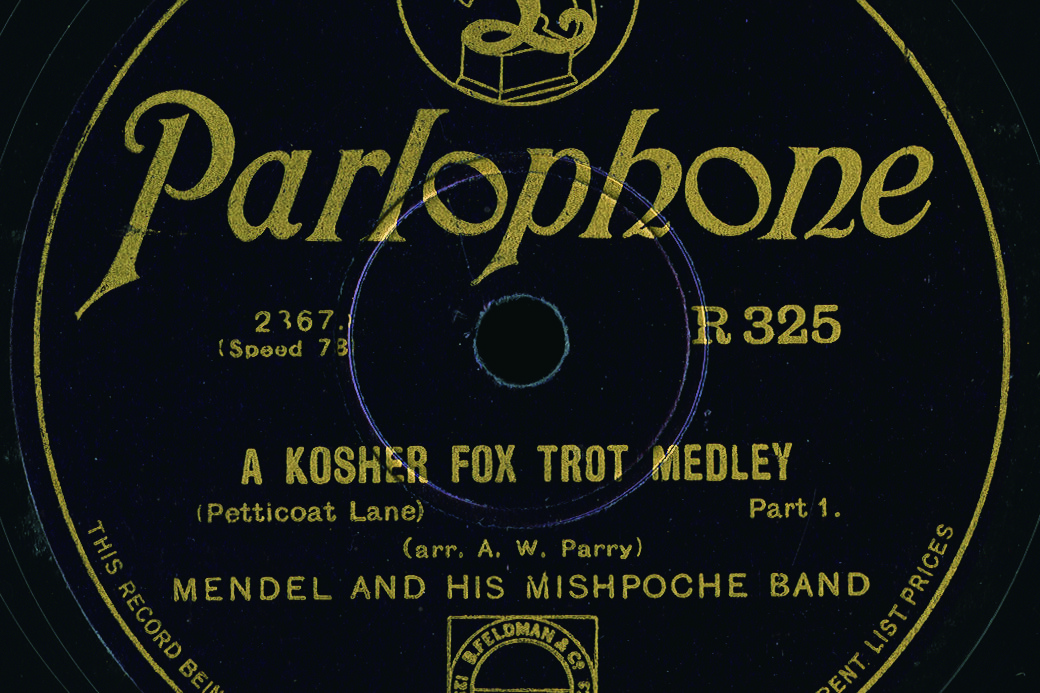

Local haunts like Petticoat Lane market were regularly name-checked in recordings and, in 1929, Mendel & His Mishpoche Band offered up lyrics sung in Yiddish to a pounding foxtrot: “The women rush to get bargains, a chicken with schmaltz, a new sock, a bit of chrain, soup, a beigel with a hole, all this you can get in the Lane / A fish-sweet, half a kishke, an onion, fish, a meaty bone, a bride with a dowry, a woman looking for a husband, such things you can get in the Lane.”

Besides bands with fictitious monikers (the musicians’ names have been lost in time), there are Jewish-themed numbers by hugely successful stars of the era. Like Whitechapel boys Benjamin Baruch Ambrose (or ‘Bert’) and Lew Stone, whose 1930s BBC Radio broadcasts made them both household names across the nation. Ambrose was born in Warsaw in 1896 and spent his early childhood in East London, but, in fear of the Zeppelins overhead in World War I, his mother packed him off to an aunt in New York. The teen prodigy swiftly rose from a member of a cinema orchestra to musical director at the Palais Royal and by the 1920s Ambrose returned to London a star. His residencies at the Embassy Club and May Fair Hotel, broadcasts and prolific recordings assured legendary status in the dance band era. In 1934, Ambrose and his orchestra recorded a foxtrot for Decca – A Selection of Hebrew Dances – a pounding medley of Jewish tunes arranged by the orchestra’s East End-born clarinettist Sid Phillips.

‘A Brivella der Mama’ (‘A Letter to My Mother’) is a popular Yiddish tearjerker, first recorded in America in 1908 by its composer and lyricist Solomon Smulewitz. As the decades passed, numerous versions flooded the stage and screen. Band leader Stone (formerly with Ambrose) even covered the song in 1933. This hauntingly atmospheric rendition of ‘Brivella’ is remarkable, as the lyrics are sung in Yiddish by the massively popular, Mozambican-born crooner Al Bowlly.

It was a treat to discover Johnny Franks and his Kosher Ragtimers, who recorded for independent label Planet Recordings, which operated from a flat in Stamford Hill in the early 1950s. As a lad Franks worked in his father’s kosher butcher shop, but by his early 20s he was composing and playing on a series of extraordinary records. His light-hearted version of Artie Wayne and Jack Beekman’s ‘Mahzel’ brings a whacky assortment of Yiddishisms and comic sound effects to a 1947 song that had already been covered in the US as an instrumental by Benny Goodman, as well as the AfricanAmerican doo wop quartet The Ravens. Franks also performs on perhaps the most wellknown and poignant track in the collection, Chaim Towber’s 1951 Yiddish classic ‘Whitechapel’. It’s a homage to a way of life that’s disappearing in front of the singer’s eyes as East London’s Jewish community disperses northwards to new suburban homelands.

We also shed a tear with Leo Fuld, the remarkable Dutch Yiddish singer whose recordings in post-war London were haunting reminders of a way of life decimated by the Holocaust. Fuld made his professional debut in the capital at the Mile End Empire, and it was while in London that he first recorded ‘Where Shall I Go?’ This is an emotionally charged anthem of the displaced Jewish people searching for a new home after World War II. The song had touched Fuld deeply when he heard a survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto singing it in a Yiddish nightclub in Paris and he vowed to make it a world hit. Lesser known, but truly exceptional is his drone-like ‘Hebrew Chant’, which was the B-side when it was released by Decca in 1949.

Stepney-born Rita Marlowe was East London’s siren of the Yiddish song. A former singer with dance bands in the prewar years, she devoted her later career to performing solely in Yiddish. Her terrific version of ‘Why be Angry Sweetheart’ (a traditional tune made famous by the Barry Sisters) is my pick of her recorded output for the Hebrew Series of Levy’s Oriole label.

The recordings on Music is the Most Beautiful Language… spin from the foxtrots of the 20s to the arrival of new dancehall crazes in the mid-50s: Brazilian samba and rock ’n’ roll. In September 1956 Oriole Records released Stanley Laudan’s Yiddish Cocktail 10” LP, just in time for the Jewish New Year. It included two particularly infectious numbers: ‘Yiddisha Samba’ and ‘Rock ’n’ Roll Kozatsky’.

Laudan, like so many of his fellow Jewish musicians, was a regular in the ballrooms of the kosher hotels of Brighton and Bournemouth (the British equivalent of the American Borscht Belt). But in the end, they saw little commercial future. That’s one of the reasons why all these tunes ended up as minor footnotes in the discographies of all those great musicians striving for success in the entertainment industry. For me, however, it’s been a labour of love researching and compiling this beautiful music. I’m sure it will be a nostalgic reunion for those who grew up listening to these songs and I hope that the music will also be a heady eye opener for a new generation intrigued by their roots, and that Whitechapel continues to be a source of inspiration and creativity.

By Alan Dein

Music is the Most Beautiful Language in the World is available now via jwmrecords.bandcamp.com, including a booklet of photos, memorabilia and Alan Dein’s essay.

Alan Dein delivers a talk about Jewish jazz history on Thursday 30 January, with guests, music and objects. 7.30pm. £15. JW3, NW3 6ET. 020 7433 8988. www.jw3.org.uk